I'm An American-Born Hispanic — What Do People Mean When They Call Me Exotic?

How Hispanic people belong, despite microaggression implying otherwise.

Craig Adderley | Pexels

Craig Adderley | Pexels I’ve been told I’m exotic on more occasions than I have toes.

“You look so exotic,” an older lady told me once at Publix in Florida. “Where are you from?”

“I’m originally from New York,” I said, deflecting the question. New Yorkers in Florida are a dime a dozen, so I doubted that alone made me exotic.

“You have an exotic look to you,” a gentleman said at Costco a few years ago. “You’ll be famous one day.”

That time, I shrugged and walked away, confused by the exchange. I’m a middle-aged, heavy-set female. What would make me famous? (Well, hopefully, my writing.)

The first time it happened was when I was a freshman at Duke in 1998. Google had just been invented, and perplexed by the comment, I remember sneaking onto the search engine and searching, “What does being called exotic mean?' Is it a compliment or a criticism? I genuinely didn’t know.

What were they trying to say about me? More importantly, what were they trying to say about the millions of Americans of Latin or Hispanic roots who look similar to me?

Hispanic people like me belong in America, so what do people mean when they call me exotic?

With age and wisdom, I finally have the answer. Although not intentional, when someone calls me exotic, they are implying I do not belong.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines exotic as:

1. Introduced from another country: not native to the place where found

2. Strikingly, excitingly, or mysteriously different or unusual

3. Of or relating to striptease: involving or featuring exotic dancers

I was born in the United States. I speak perfect English. I have dark hair and dark features; does that make me “not native” or “unusual”? Or perhaps my robust belly makes me an ideal striptease candidate? What exactly about me is “exotic”?

My mother comes from a long line of Northern European immigrants, including Irish and Swiss. My grandmother can trace our family history to the Sons of Liberty. Like her mother, she was a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

My father, however, was born in El Salvador. He immigrated to the U.S. in the 1970s. I was born on Long Island — about as far away from exotic as you’d imagine. As a baby, I had jet-black hair and pale white skin. My mother said I looked like Snow White.

As I aged, summers spent running through sprinklers turned my skin brown. Because of our contrasting complexions, people would ask my mother if she was my nanny. As an adult living in Florida, I am generally tan year-round. My hair and eyes are also dark brown.

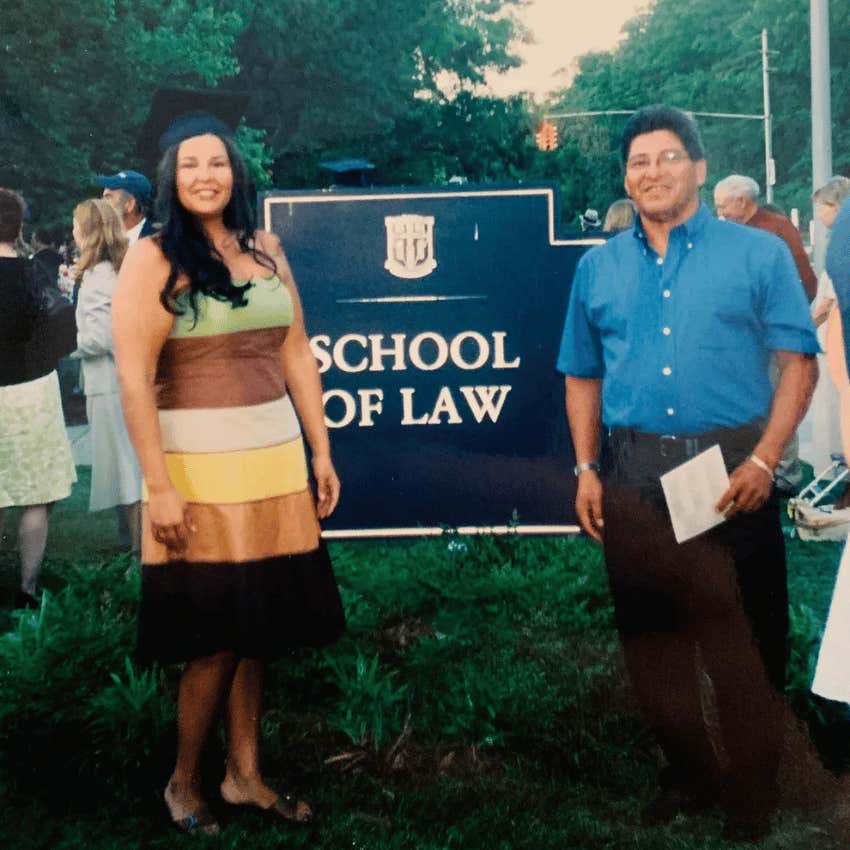

Photo from Author

Photo from Author

Is that what makes me exotic — because my skin and complexion are not fair? If that is the case, why do we feel that being Brown is not American?

A microaggression is a “comment or action that subtly and often unconsciously or unintentionally expresses a prejudiced attitude toward a member of a marginalized group (such as a racial minority).” These statements reinforce stereotypes, i.e., that brown people are not native to the U.S.

I’m very proud to be part Hispanic. Straddling two identities allows me insight into two different cultural worlds. But being told I’m exotic implies that I don’t belong in the country where I was born. I try not to be offended, but deep down, it pokes at my sense of self. It makes me question how I’m seen and valued.

Unsurprisingly, I was first told I was “exotic” while a student at Duke University. Although I graduated as the valedictorian of my high school, I still felt I had to justify being at an elite college. They didn’t think I fit in. (While at a computer lab, another student whispered that I had the most “beautiful hair” she had ever seen, so not all my experiences were bad.)

Somehow, my brown hair and tan skin stick out as foreign in a country composed of immigrants from different backgrounds. Many people who immigrated to the United States came from places much further away than El Salvador.

I’ve seen Far and Away one hundred times. We all know about Irish immigration during the 1800s–1900s. Up to 4.5 million Irish arrived in America between 1820 and 1930 alone.

That makes my Irish roots as foreign as my Salvadoran ones. The Irish immigrants experienced discrimination and exploitation upon their arrival as well, although the extent is still debated.

Still, once they lost their accents, it was easier to assimilate into society because they were white and spoke English. This applied to many Northern European white immigrants. Non-white and Hispanic immigrants have not been as lucky.

Photo from Author

Photo from Author

I’m exotic not because my father was an immigrant but because my father was a Brown immigrant.

During my childhood and adolescence, I saw my father face stereotypes time and time again. My father became a U.S. citizen in the 1980s. After working as a cook in diners for years, he and my mother opened a pizzeria. He spoke English, Spanish, and Greek fluently.

He read the newspaper every day to improve his language skills. He voted in every election and took great pride in being part of the political process. (Though he voted for candidates I disagreed with, I admired his sense of social responsibility.)

Yet, customers would come into his pizzeria and talk to him in broken English. They assumed he was uneducated because of his skin color, black hair, and dark eyes. He would always respond to them in the same. I would listen in shock.

One day, I told my dad, “Why don’t you tell them you speak English? Why are you belittling yourself?”

I wanted him to stand up for himself. He worked so hard to assimilate and be American.

He shrugged. “They see what they want to see,” he said. And all they saw was that he was Hispanic, so he was illiterate and uneducated.

We went to El Salvador in the summer of 1998 to celebrate my high school graduation. Upon returning to the United States, my father was asked by immigration officers to write down his social security number and other information. They questioned him heavily about the brooms he was bringing into the U.S. to clean the pizzeria.

Again, I was defensive. He had a U.S. passport and was not bringing in any banned items. Why were they singling him out in front of his family, nonetheless? I learned later they do that because if someone is using a stolen passport, they will be confused when questioned about specific details.

That appalled me even more. I’d just graduated first in my class, and they treated my father like he was last in his class. But my father did what he was told. He did not question them at all.

Photo from Author

Photo from Author

My father didn’t challenge his place as an immigrant. He accepted that he was a foreigner. What he didn’t anticipate was that his U.S. citizen children would still be questioned.

A 2021 study published by the American Psychological Association explored whether people’s skin tone affects how perceivers categorize their immigration and legal status and the potential link between perceivers’ support for stringent immigration policies and specific categorization patterns.

Results suggest that people with Brown (vs. white or Black) skin are more likely to be perceived as undocumented immigrants and that perceivers’ ratings of an individual with brown skin as more likely to be an undocumented immigrant predicted higher levels of support for harsh immigration policies.

Pew Research reported that in 2021, only one-third of all U.S. Hispanics were immigrants, meaning that two-thirds of U.S. Hispanics were U.S.-born. From 2020 to 2021, U.S.-born Hispanics outpaced the arrival of new immigrants. The same report noted that “immigrants are a declining share of the U.S. Hispanic population.” Furthermore, 81% of Hispanics in the country in 2021 were U.S. citizens.

Despite these numbers, the impulse is still to assume that Hispanic people are immigrants or foreign. With European immigrant groups, generations assimilate, and over time, their status as Americans is not challenged. But non-white immigrants, some of which have been here for generations, still have to prove their worth.

I used to hold these stereotypes as well. Before I went to Duke, I thought all men who looked like my father shared his history. But I learned that is not the case. Whether it was the Mexican-Americans living here before and after the Mexican-American War, the Chinese immigrants who laid half the railroads, allowing Manifest Destiny to prosper, or the Black people whose forced labor laid the foundations for American prosperity, diverse citizens have always played an integral part in our nation’s history.

The greatest part of our country is our diverse roots. The U.S. is a melting pot — yet for some, they are still singled out.

I write this piece to normalize the idea that Hispanic and Latin people, as well as other non-white immigrants, belong. Having a darker or different complexion does not mean someone is exotic or foreign. It’s a form of microaggression that many might not realize.

Unless I’m wrong, and they are calling me “exotic” because they think I have the build and arm strength to be an exotic dancer. After all, you never know.

Julie Calidonio is a writer, lawyer, and mother. Her essays published in Scary Mommy, Motherly and Medium highlight her comedic yet poignant writing style.