I Was Born In Korea, But I Buy My Kimchi At Costco

My fear of failing as a Korean parent.

Courtesy of Author, Bianca Birau's Images | Canva

Courtesy of Author, Bianca Birau's Images | Canva “I’m going to help plan the first Lunar New Year Celebration in Edmonds!” Caitlin announced to my husband and me at the dinner table one night in December 2021.

“That’s great, Caitlin!” I beamed at my 17-year-old daughter. In our two decades of living in the predominantly white suburb of Seattle, this was the first official Asian cultural heritage celebration, a huge milestone.

“Way to represent, Caitlin!” Andy said.

Then I thought, But we don’t celebrate Lunar New Year! Our family rang in the new year on the Western calendar. On Lunar New Year, we were lucky if I remembered to grab sweet rice cakes at the Korean grocery store. How could Caitlin mark something she didn’t know?

For weeks, Caitlin was immersed in preparations–attending meetings, securing art supplies, and marathon painting to finish the art installation with other volunteers. She updated me on the program: lion dance, Kung Fu demonstration, movie screening. She brought home posters with a bright red background, typically associated with Chinese New Year. I thought: Where is the Korean part in this celebration? I held my tongue.

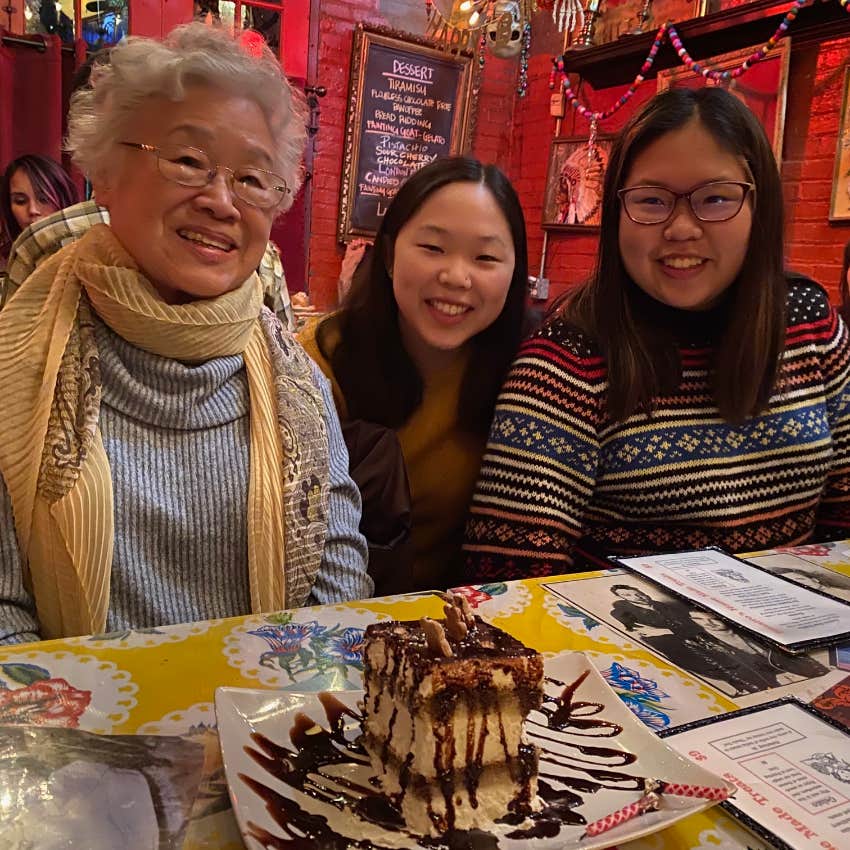

Photo by author

Photo by author

A few days before the event, Caitlin showed me the event website with “Happy New Year!” written in seven Asian languages. “I wanted to make sure Koreans were represented,” she proudly pointed to the Korean greeting.

“How do you pronounce Happy New Year in Korean again?” Caitlin asked.

Oh dear. I thought back to the January 1st New Year celebrations of the past with my mom helping Caitlin and Ella sound out saehae bok manee badesaeyo during Sebae, the Korean New Year’s bowing ceremony, their words slipping on their tongues like foreigners. Despite practicing, the girls mangled the pronunciation as they bowed to their grandmother. My mom laughed as she blessed them, handing them a white envelope of New Year’s money.

Here Caitlin was representing Koreans, and she didn’t know this basic Korean phrase. Was I failing as a Korean parent? Maybe we should stop buying kimchi at Costco.

With my mom passing away six months ago, I feared we were becoming inauthentic Koreans. I remember feeling inadequate at Mom’s funeral when I switched to English to deliver her eulogy, the adopted language more comfortable than my native tongue. Seeing my child’s name on the Lunar New Year Celebration website, a presumed authority on our culture, I felt like an impostor.

The night before my older daughter Ella left for her trip, I stood in the middle of an Asian supermarket, looking for a gift for her friend’s family hosting her. My mother’s mantra “Never show up to somebody's house empty-handed!” had been ingrained in me.

I surveyed the isle of teas. I looked for boxed fruit sets, unsure what kind of gift they would appreciate.

“Are Rina’s parents like, Asian-Asian? Or are they like us?” I asked Ella, putting air quotes around the phrase Asian-Asian.

Like us–Asian Americans with looser cultural practices — kind of like non-practicing Catholics.

“Do these green tea bags look too cheap?” I held up the shiny foil packaging to my husband. Andy shook his head, growing impatient after half an hour of these questions.

I wondered what my mom would say. She had taught me to thank my college professors with thoughtful, personalized gifts. She had always been my on-call advisor, not only on gift-giving etiquette but on all things related to my Korean heritage. With her gone, who would help preserve our cultural legacy through the generations?

Photo by author

Photo by author

What if we inadvertently offended her hosts by striking the wrong note? I shuddered, imagining the judgment. What kind of Asian family sends such a cheap gift after foisting their kid on us for days?

I recalled my faux pas at my uncle’s 90th birthday lunch when I had forgotten about the custom of presenting cash gift envelopes. Having been a teenager when my family immigrated, my Korean cultural education had been stunted–just enough to know I wasn’t quite getting it right.

“No, these tea bags won’t do,” I said. I had to do right by Mom’s legacy.

“Let’s go to Fran’s Chocolates. They’ll have a nice gift set,” I said. My family groaned loudly.

During the drive over to Fran’s, I blurted out, “Ella, you can’t sleep in until noon as a guest in somebody else’s house, you know that, right? And be sure to help with the dishes and stuff!”

“Mom, I know!” She rolled her eyes.

Though Ella is considerate, I felt creeping anxiety about whether I had prepared her to navigate cultural etiquette with an Asian family we didn’t know.

We arrived at Fran’s Chocolates and made a beeline for the boxed set section.

“$40 for 20 pieces of chocolate?” I gasped aloud.

Ella protested, “Mom, it’s not worth it!”

I wondered whether Rina’s family were the type of Asians who would appreciate the fancy brand name chocolate or find such a purchase frivolous.

I remembered shunning the brand-name-obsessed talk dominating the lunch table at the Korean church. As my pragmatic mother’s daughter, I was the only one who didn’t care about owning a Louis Vuitton purse. And here I was dealing in chocolate prestige.

Though I wouldn’t normally indulge in such an extravagance, I bought the $40 box for my daughter’s hosts, in case they cared about such a thing. It may be too late for a crash course on proper Asian houseguest conduct, but this was something I could do to help make a good impression.

When we showed up for the Edmonds Lunar New Year Celebration, the streets were packed with hundreds of people. Caitlin and others stood out in their bright red Edmonds Lunar New Year sweatshirts–taking pictures, cueing up the Mayor’s introduction, and talking to the performers. Cheers roared during the lion dance; families of all races lined up to participate in the Kung Fu demonstration. People flocked to the booth selling posters and event apparel, merch selling out like a rock concert. They had managed to make an Asian cultural celebration a cool thing.

Afterward, Caitlin huddled with fellow planning committee members, celebrating the successful event. I gushed about how they pulled off the event with vision and grit. Caitlin beamed with pride, and my heart swelled. I was struck by the significance of this group representing various Asian heritages coming together to put on this cultural event in the backdrop of the tense political climate after the last few city elections. Many were disappointed due to the more diverse, progressive candidates losing to conservative white candidates who promised to preserve the small-town feel.

I chewed on the word “preserve,” and realized I had been thinking about it all wrong.

Caitlin had poured herself into preparing this beautiful celebration of her Asian American heritage. It was a labor of love full of pride, not anxiety about performing the correct rituals. Though my mom was gone, Caitlin’s pride in our culture was deeply rooted, just as Ella didn’t worry about having to prove her Asianness with a fancy gift. Ella was charting her path of cultural exploration in college, taking Korean classes and learning to cook her grandmother’s favorite dishes. Mom’s legacy was alive and well; the girls were just defining their adaptations.

Photo by author

Photo by author

I see now that their versions of Korean American identity will look different than my own, not less. Maybe I need to let go of the hang-up about preserving an “authentic” cultural legacy and embrace the evolution of our Koreanness.

We weren’t Asian-Asian after all.

Terri Chung is a writer and an English Professor at North Seattle College.