My Parents Tore Me From My Home, And My Grief Caught Up With Me 32 Years Later

Leaving communist Czechoslovakia changed my life forever.

Kseniya Ivanova | Shutterstock

Kseniya Ivanova | Shutterstock “Go ahead. Tell them.” My stepdad nodded at my mother.

She turned to look at the three of us in the back seat of the Lada. “Your dad…we…” She pinched the bridge of her nose and sighed. “George…I can’t.”

We had just left the Hungary/Austria border crossing, and I knew, deep in my gut, that something was wrong. My parents lied to the border guard about why we were entering Austria. They told him my little sister was sick and that we had to get back home via the shortest route possible, which is why we were now in Austria, a country we had no business visiting.

None of this made sense. We were supposed to be going camping on the shores of the Black Sea. Instead, we’d been driving for days, visiting relatives in Hungary and stopping off in Yugoslavia to get documents to enter Austria.

We were from communist Czechoslovakia, and everyone knew that traveling to countries beyond the Iron Curtain was prohibited. Austria was one of those countries. What were we doing here?

“Tell them!” my stepdad repeated. “I’ve got my hands full here.” He motioned at the rain-streaked windshield, its wipers losing the battle against the deluge of rain that made the Alpine highway as slick as ice.

It was August 1979, only a week before school was to start. I hadn’t wanted to go on this impromptu vacation to Bulgaria and asked to stay home. My stepdad refused.

I knew better than to take on his tight jaw and don’t-mess-with-me stare and grudgingly crawled into the back seat of the Lada with my stepbrother and little sister. I was 13, years away from being able to challenge my parents on what they thought was best for me. Their plans became my plans, regardless of how much I wished otherwise.

Mountains dwarfed our Russian Lada on both sides of the highway and the clouds, dark and ominous, rolled down hills like sleepy ghosts. I touched my mother’s shoulder. “What’s going on?”

She shook her head and turned to look at me. I could see it in her eyes. Whatever was coming next was bad.

“We’re not going on vacation. If everything goes according to plan, we’ll be moving to Canada in a few months.” Her gaze slid from me to my stepbrother and then my little sister. “Do you understand?”

Her words entered me like pain entering a fresh wound. The rain outside grew manic. I heard my stepfather’s palms unstick from the steering wheel, the chatter of the windshield wipers, the tires sluicing through the downpour on the highway. My head was full of sound.

“Are you okay?” my mother’s voice sounded far away. “Judy?”

“But when are we going back home?”

“We aren’t.”

“Ever?”

“Never.”

This conversation marked the end of my childhood innocence. I went mute for two days. When in quarantine at the refugee camp in Traiskirchen, I couldn’t stop crying. The feeling of helplessness and hopelessness was unlike anything I had ever experienced.

My parents refused to send me back home.

I was a child. They knew what they were doing. I’d thank them later. The life that was waiting for us in Canada was going to be grand. They told me I was brainwashed at school by propaganda. None of what I’d been taught about capitalism was true. Everything I believed about communism was a lie.

I eventually accepted the reality imposed on me by my parents. I learned English, adapted to a new culture, and sang the Canadian anthem when we took the oath and became Canadian citizens in 1982.

What I didn’t do was grieve the loss of my homeland and my innocence.

My grief caught up with me 32 years later. My husband, our 12-year-old daughter, and I returned to do a final clean of a house we had lived in for 13 years. The move had been my idea. I was in denial of our failing marriage and thought a change of residence would help shift things.

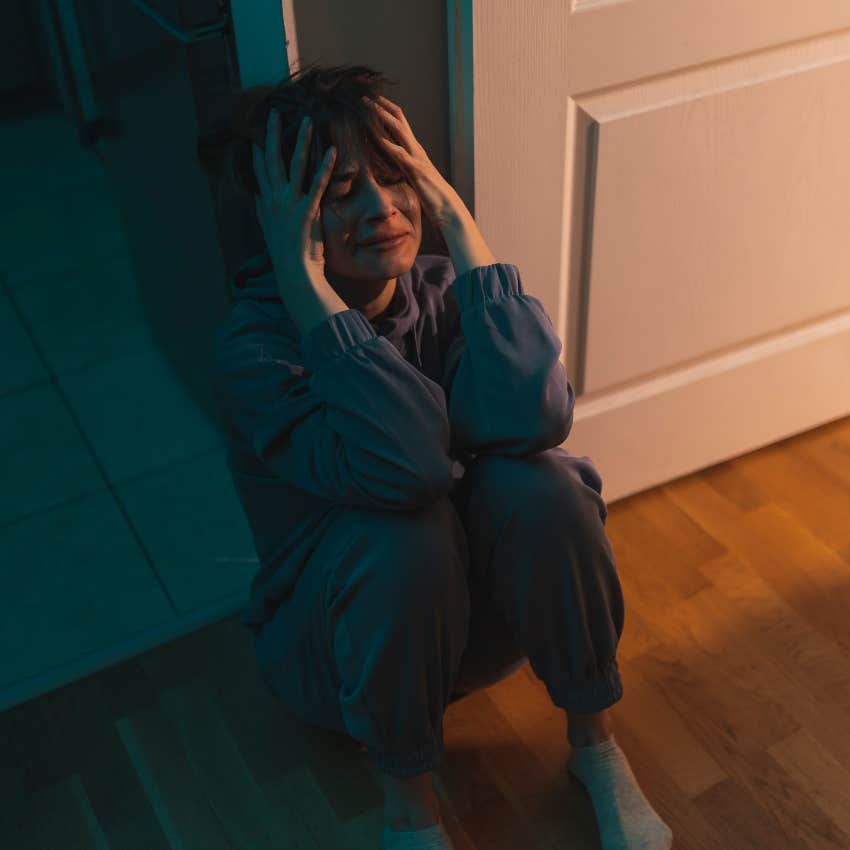

While wiping the baseboards and sweeping out the corners of the rooms, I experienced a boggling breakdown. My daughter sat next to me on the floor and held me while I sobbed uncontrollably. The grief I felt was immense. Everywhere my gaze landed confirmed that it was too late. I’d never be able to return.

Impact Photography / Shutterstock

Impact Photography / Shutterstock

This house had been my home for 13 years. My husband and I got married in the backyard. Our two children were born in the master bedroom. Christmases and birthdays were celebrated in the living room and thousands of meals were prepared in the bright kitchen. Our children learned to walk and talk here.

“Nonononononononononononono,” is all I managed between sobs. My daughter, terrified by my tears, summoned my husband.

“I knew there’d be regrets,” he said and walked away, back to cleaning out the garden shed. He hadn’t wanted to move and silently blamed me for all the trouble.

Could I pray for a miracle? I wanted to rescind the acceptance of the sale and back out of the purchase of the new house, even though I knew that was impossible. I was feeling the same helplessness I had felt inside the Lada.

The sorrow that found me sobbing on the living room floor was the sorrow I hadn’t allowed myself to feel when, at 13, I was told I couldn’t return home to Czechoslovakia.

Those two moments were pivots in my life. The first one, at 13, led to a radical shift in who I believed I was. It taught me to be curious, to ask questions, to trust my intuition, and to arrive at my conclusions.

The second pivot occurred when I realized we will always be offered another chance to feel and heal. Sooner or later, those unhealed traumas will surface and ask us to feel what we couldn’t in the past.

Judy Walker writes about the gritty, lovely, naughty, and joyful bits of humanhood. She has written extensively for Medium and Elephant Journal.