I Am Losing My Sight — 4 Things It Taught Me About Living The Life We're Dealt

At 16, my ophthalmologist told me I would likely be blind by thirty.

Courtesy Of Author

Courtesy Of Author At 16, my ophthalmologist told me I would likely be blind by thirty. He advised me to prepare for life with little to no sight. He had told me the future, or so I thought.

“You have Usher Syndrome.” I had never heard of it before — a disease-causing hearing loss and eventual blindness. I completely crumbled, burying my face in my grandfather’s chest, soaking his sweater, as my mother struggled to hold back tears. One of the doctors leaned forward to give me a tissue, I can still remember how uncomfortable and awkward he looked.

I went into that hospital as an adventurous, social, and daring teenager — the kind of boy who loved pranks, parties, and girls. I had so much going for me. But I left as someone completely different.

To this day I cannot articulate exactly what changed in me, but it felt like I was being followed by a dark cloud wherever I went. I had intended to do great things with my life, but now the future seemed like an abyss I was looking into. My sight loss was a source of grief, and with every cluster of retina cells that died, the grieving process would start all over again.

But this is not a pity story — you will find out below how much I have come to dislike pity. This is a story of hope and inspiration. The capacity of the human mind to overcome hardship is astonishing. But to overcome hardship, I had to embrace it. To face it completely without trying to make light of it, without sugarcoating it. It is in surrender that we learn the greatest life lessons.

Here are four things losing my sight has taught me about living fully:

1. Most people are happy to help you if ask for it

My grandmother always says: “If you don’t ask, you don’t get.” Growing up, whenever she said this it was mostly about all the chocolates, ice cream, and other goodies she had stored away. However, I believe it is also a great life philosophy.

When it came to my sight loss, I used to be embarrassed to ask for help. I would take unnecessary risks such as crossing a busy road, which is difficult and dangerous for me. With no peripheral vision, it is easy to miss cars, cyclists, curbs, and pedestrians.

It can feel extremely overwhelming to try and be aware of so many different things within such a small field of vision. My heart would be pounding as I stood on the sidewalk, too proud to ask for help. It led to many accidents that could have been avoided had I just asked for help. But over the years, I have learned, albeit via the hard route, that most people, even strangers, are more than happy to help. I just need to ask.

Whether it is asking a stranger if I can place my hand on their shoulder to help me navigate, asking a friend for emotional support, or dropping my masculine pride and asking my girlfriend to “take my hand and guide me” through a dimly-lit bar, I have learned that it is vital — and okay — to ask for help when you need it.

Never be ashamed, embarrassed, or shy about your needs; everyone has them, and the world is full of people who are happy to help you. Think of it as an exchange of positive energy — you feel better having been helped, and the other person feels good for having helped.

2. Pity gets you nowhere

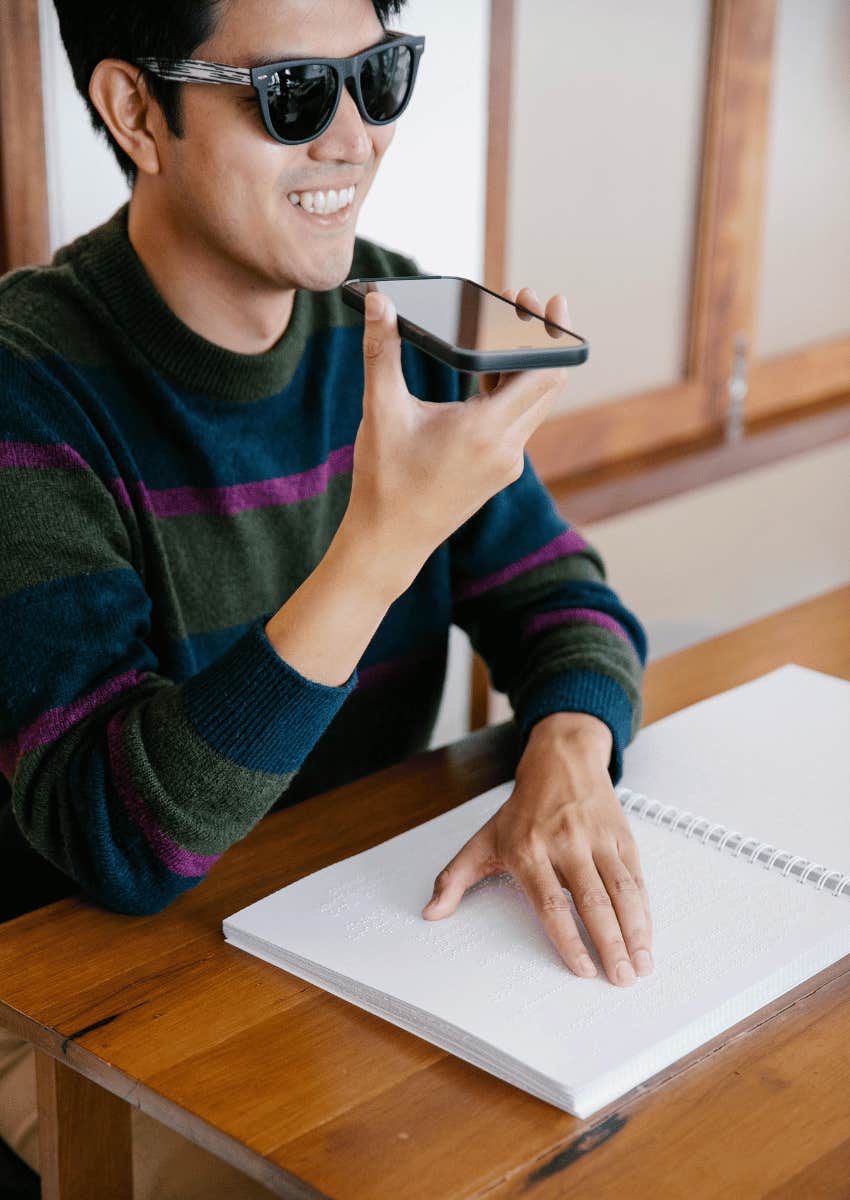

Eren Li | Pexels

Eren Li | Pexels

There was a time in my life when I welcomed pity. It felt like permission from other people to feel bad, it made me feel supported in my feelings of anger and resentment. But pity is the thief of accountability. Whether it is self-pity or pity coming from another person, the only thing pity does for us is prevent us from taking responsibility for ourselves.

My mother struggled with my diagnosis and blamed herself. Talking to her about my struggles would often make her cry, so I learned to bottle things up. My mother felt incredibly sorry for me and this became a self-fulfilling prophecy — I started to feel sorry for myself, too. I became a passive person who lacked self-belief and confidence, losing the ability to weather a storm and take on life’s challenges.

It was only many years later I decided I had had enough. I was deeply unhappy, and lonely and had a strong sense that life was passing me by. I realized that the pain my mother felt was her own and was separate from me, and while I love her very much, I could not bear both of our crosses. Her being unable to cope did not have to mean that I couldn’t cope.

It became apparent to me that I was unhappy about my circumstances and yet entirely responsible for them. I would no longer sit idly and wallow. My home would no longer be my bedroom but the whole wide world outside of it. I needed to surround myself with people who inspired me; who I could inspire. People who I could learn from and experience new things with. To be someone who lives life in spite of his difficulties rather than with them.

Do not confuse pity with empathy, which is the ability to understand and share the feelings of another person. But pity is something given, not shared. Feeling truly supported and understood comes out of compassion and empathy, which are feelings that have their roots in love.

We are all dealt our deck of cards that are unique to us. You cannot return them to the store, nor can you swap them with another person’s deck. What you can do is face the facts of your life and work with what you have. Understand that you do have it within you to do the very best that you can.

3. Worrying creates the illusion of having control

How many great minds would the world have been robbed of if they had succumbed to their worries? If Stephen Hawkins hadn’t persevered despite being told he only had a few years to live, we wouldn’t have had one of the greatest physicists of our time. JK Rowling might never have persisted with her writing. Rosa Parks may never have sat on the “white person’s” chair.

I spent so many years worrying. About how many years of sight I have left, about never being loved romantically, about being a burden to those around me. Our life is finite and the time I had spent worrying is time I will never get back. It was time I could have used to better myself, to enjoy my life, to focus on the good things I had.

Yet here I am today, typing this on my laptop with my incredible girlfriend working in another room, and my dog, Lou, bugging me to go for a walk. But to achieve these things, I had to start taking accountability for myself, which meant realizing the futility of worrying about things outside of my control. Mark Twain nailed it when he said: “I’ve had a lot of worries in my life, most of which never happened.”

Looking back, I realize how pointless all that worrying was. No one knows what is going to happen tomorrow, let alone years from now. I often remind myself that the past is dead, the future does not exist, and all we have is now.

Of course, I am not without worries these days, but I pay close attention to whether a worry has any basis in the present moment. If it does, then I do something about it. If I can’t do anything about it, then I leave it for a future me to be concerned with. He can handle it.

So I would like to encourage you to do the same. The next time you find yourself worrying, try casting some doubt over the worry. Question it, challenge it, and ask yourself if it is a problem that can be solved right now. If it isn’t, then realize that you are trying to fix something that does not exist in the present.

4. It is a miracle that we are even here, so cherish your life

Rogério Souza | Pexels

Rogério Souza | Pexels

As I look back on my journey, from the initial diagnosis to navigating life with progressive vision and hearing loss, I’ve come to understand something profound: life is fragile, fleeting, and above all, it is a gift.

It wasn’t until I faced the reality of losing my sight that I truly began to experience the world differently. My limitations gave me a deeper appreciation for each moment. Every walk with my dog, every conversation with a friend, every night cuddled up in bed with my girlfriend — all of it is so precious and I try my best not to take these things for granted.

In my younger years, I wasted so much time worrying about what I would lose, instead of focusing on what I still had. But through accepting my condition, I came to realize that despite the difficulties we face in this imperfect life, life is something rare and incredibly valuable. The odds of any of us being here are astronomical — 1 in 10²⁶⁸⁵⁰⁰⁰ to be exact — an incomprehensible number. We are a miracle of existence, and every day is an opportunity to live by that knowledge.

We get one shot at this life, and while none of us know exactly what the future holds, we do know that we have this moment right now. So dear reader, I encourage you to live fully, courageously, and authentically. Take those risks. Discover who you are and the world around you. Dance in the rain, laugh with strangers and cherish the small things in life that often go unnoticed.

Let go of perfectionism and the need to have all the answers. Instead, focus on being present, being kind to yourself and others, and recognizing the beauty in the now. Life will always bring challenges but those challenges are part of what makes our journey so rich and meaningful.

Even as my vision dims, I see more clearly than ever that the beauty of life isn’t in what we have or lose, but in how we choose to live out each day. I may eventually lose my sight, but I do not have to lose my mind.

Today I am 33 years old and I live in Budapest. I still have some useful vision and my hearing loss is corrected with hearing aids. I am happy and lead a fulfilling life. I have traveled extensively, sung and played guitar in bands, and I have met and met some wonderful people in my life. Through my journey, I’ve come to understand that the greatest life lessons often come from our darkest moments.

Mario Georgiou is a mindfulness teacher and disability advocate, passionate about exploring the inner landscape of resilience and acceptance. A recent arrival to published writing, he writes with a fresh perspective and a sincerity that deeply resonates.