3 Enchanting Japanese Words That Will Immediately Brighten Your Day

Disclaimer: No ikigai, kintsugi, or wabi-sabi included.

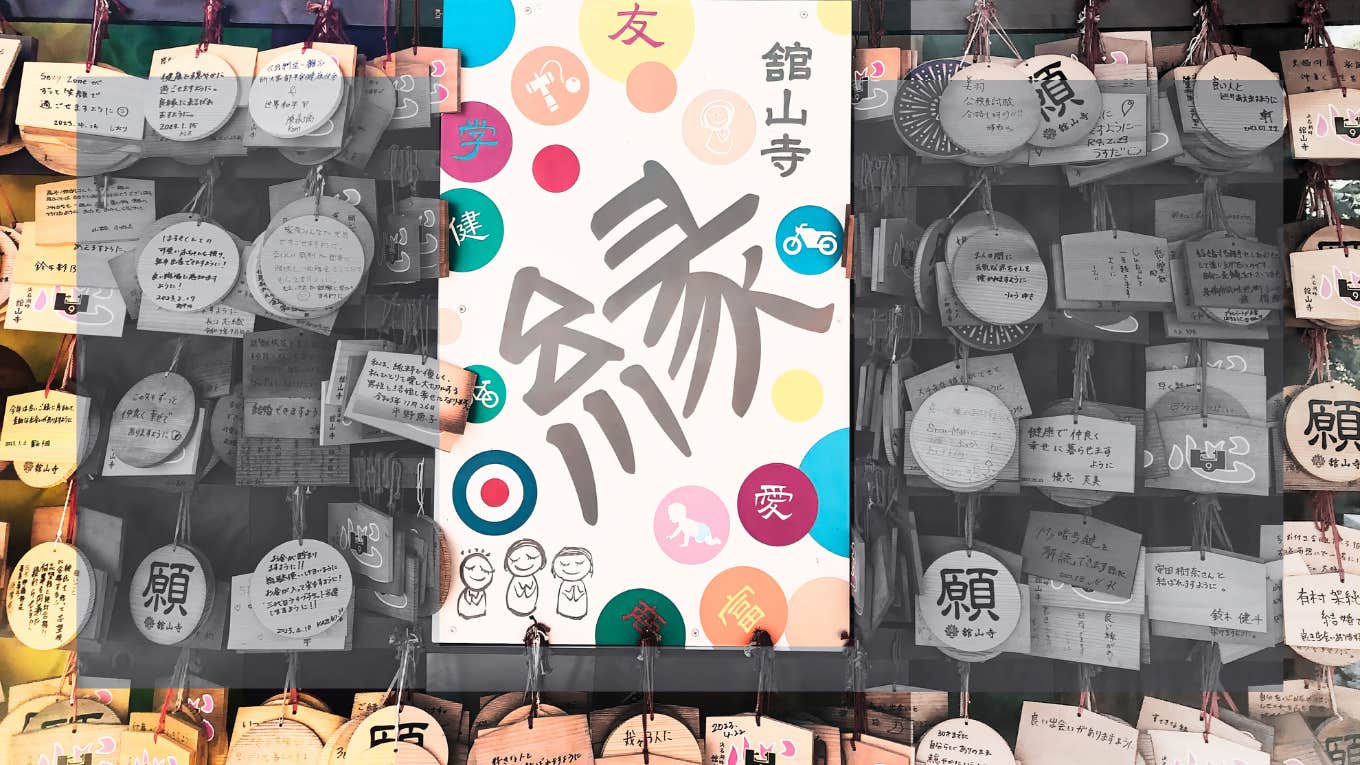

Courtesy Of Author

Courtesy Of Author As a native Japanese speaker, I get annoyed when I come across English articles that tout Japanese buzzwords like ikigai. They’re not commonly used in our day-to-day conversations. Ikigai is more like a stock word thrown in job interviews or autobiographies.

Instead of those fancy words, I’d like to introduce my three favorite Japanese words. They’re basic words but each carries a cultural richness that defies translation into a single English word.

Here are 3 enchanting Japanese words that will brighten your day:

1. En (縁) / Goen (ご縁)

If you’re familiar with the Japanese language, you may know that people toss a five yen coin into a donation box at a shrine. They wish for good “en”—not cashback in yen—but fortunate connections with people and new opportunities.

En (縁) can be roughly translated to words like destiny, bond, or connection. What’s intriguing is that 縁 isn’t as casual as accepting someone’s connection request on LinkedIn. The word has a slight nuance of serendipity and a more profound notion of fate.

An old saying explains this perfectly:

袖振り合うも他生の縁 (sode furiau mo tashō no en)

The accidental brushing of sleeves can be a predestined encounter in this life

Sode suggests the sleeves of the kimono, and tashō means our previous lives. This proverb is a reminder of how important it is to embrace each encounter with new people mindfully.

That said, I have to mention that the sense of serendipitous encounters has been diminishing in our modern lives. On a crowded train during rush hours, we all hope to avoid touching others’ clothes.

Nevertheless, if you want to deliver a formal speech expressing your gratitude for the connections you’ve made, you can say,

ご縁をいただきありがとうございます (goen o itadaki arigatō gozaimasu)

Thank you for the connection.

En can also come into play when you feel a special affinity with someone. It often carries romantic connotations, and you can use a phrase like this to convey your hopeful feelings:

あの人とは縁があるような気がする (ano hito to wa en ga aru yōna ki ga suru)

I feel like I have a predestined connection with that person.

2. Otagaisama (お互い様)

The Japanese word otagai (お互い) simply means “each other”, but when the honorific sama (様) is added, it suddenly means so much more.

There’s no direct English equivalent, and it’s often rendered as a scenario where two parties are in the same boat and mutually supportive. The nuance is close to, “I know you’d do the same for me.”

It may sound not entirely selfless, but the speaker’s intention is usually to ease the emotional burden of the listener who might feel indebted for assisting. The following saying captures the sentiment well:

困った時はお互い様 (komatta toki wa otagaisama)

We support each other when in trouble

The comfort this phrase can carry is tremendous. In my case, I owe a lot to my mother’s caregiver, yet she graciously declines any gifts and uses this phrase instead. We both know it can’t work the other way around because she’s a professional caregiver, but the phrase still serves to enrich our communication, for which I feel truly grateful.

This word encapsulates the principle of Japanese communication because it can be used negatively, too, when two people are fighting. The collectivistic culture can be controversial, but the shared spirit of cooperation is undeniably valuable.

3. Omomuki (趣)

If you have heard of wabi-sabi, it’s easy to understand this word. Omomuki roughly means grace, charm, and refinement. The typical phrase is,

趣がある (omomuki ga aru)

It has a graceful taste.

The judgment of whether it’s omomuki-bukai (趣深い)—tasteful or not—is highly subjective. Wabi-sabi focuses more on ephemeral beauty, but omomuki suggests a broader sense of modest grace.

When I travel, I usually try to find places with omomuki rather than focusing on Instagrammable eye-catching spots. This way, I can relax and immerse myself in the local vibes.

For instance, Kyoto residents take great pride in their lives filled with omomuki and often look down on Tokyoites. To them, Tokyo appears as a jungle of concrete buildings flooded by job seekers without much historical value.

Another point on which most Japanese people would likely agree is that Ginkakuji Temple is more omomuki-rich than Kinkakuji Temple. The gold-plastered Kinkakuji is too glitzy. Omomuki shines more modestly and gracefully.

Photo: Ginkakuji Temple/Pixabay.

Bonus Word! Tsundoku (積読)

As a book lover, I can’t finish this article without mentioning tsundoku. It’s a portmanteau derived from the verb tsundeoku (積んでおく), which means piling something up and putting it aside.

Japanese bookworms have shortened the word by replacing the latter part of the word with the kanji 読 (doku), which means reading. This linguistic maneuver describes the habit of piling up unread books.

As I mentioned in my piece for The Japan Times, tsundoku is a guilty pleasure cherished by many book enthusiasts.

Yuko Tamura is a writer, cultural translator, and the editor-in-chief of Japonica based in Tokyo. Her articles have been featured in The Japan Times, Unseen Japan, The Good Men Project, BBC Radio, and more.