How To Apologize To Someone You Hurt, According To Psychology

Simply giving an apology isn't always enough.

Getty

Getty By Matt Berical

“Love means never having to say you’re sorry ...” Could there be a more worthless platitude?

When you’re in a relationship, especially for any significant period of time, you will eventually have to apologize for something, as fights and misunderstandings are inevitable.

There are different ways to apologize, for sure.

There’s the “Oh, sorry”-apology you cast off when you just want to get someone off your back (and you aren’t really sorry).

There’s the blunt “I’m sorry! OK?!” when you sort of mean it, but that doesn’t really do any good because, let’s face it, if you only sort of mean it, do you really mean it at all?

Marriage and couples counseling expert Larry Michel explains, "Most apologies are not delivered for the benefit of the person to whom harm was done. More often they are delivered so that the person who inflicted harm feels better about themself despite their actions."

Being on the receiving end of a non-apology apology sucks.

If we're being honest, though, we've all done it. And there’s a time and place for it.

But when you truly need to apologize for something you’ve done that has painfully hurt your partner, you need to understand what comprises a genuine apology.

What makes for a sincere, effective apology?

You have to mean it, sure. But, there’s a narrative structure that a good apology should follow.

Roy J. Lewicki, professor emeritus of management and human resources at Ohio State University’s Fisher College of Business and a leading scholar in the study of negotiation, trust development and trust repair, and conflict resolution, served as lead author of a 2016 study on what makes for an effective apology.

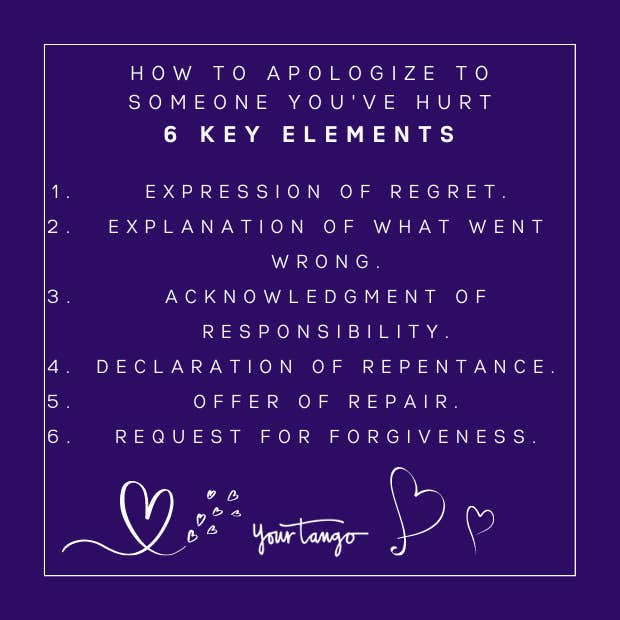

Their report identified six distinct components that make up an effective apology:

Expression of regret

Explanation of what went wrong

Acknowledgement of responsibility

Declaration of repentance

Offer of repair

Request for forgiveness

By making sure to incorporate these six components in your own request for forgiveness, you’ll be able to craft an apology that really, truly means something.

It may sound a little complex at first glance, but Lewicki explains that, when followed properly, these six steps are not only simple, but effective.

In a press release that accompanied the publication of the study, Lewicki noted, "Our findings showed that the most important component is an acknowledgement of responsibility. Say it is your fault, that you made a mistake."

He said the second most important element was an offer of repair.

We asked Lewicki to break down each one and explain how and why they work so well, then used his responses to create this helpful guide.

How to Apologize to Someone You Hurt

1. Offer an expression of regret.

To start, you must tell the other person that you’re sorry for what you did.

It’s important that you get this part right because it will set the tone for everything that follows.

Tone is crucial. If you sound insincere, sarcastic, or otherwise disingenuous, then whatever else you have to say next will ring hollow.

“What this does from the speaker’s point of view is try to express how sorry they are for the offense,” Lewicki explains. “This is where tone can make a difference. You can say, ‘I’m really genuinely sorry,’ and communicate some emotionality in that. Or you can be sarcastic and say, ‘I’m sorry, did I offend you?’ and totally diminish the content of your apology.”

2. Provide an explanation of what went wrong.

Here is where you have a chance to explain your side of the story and try to let your spouse or partner know that, whatever mistake you made, there was a reason behind it.

This can go a long way toward letting your spouse see what your thinking was behind your actions and perhaps change their perspective on why they’re upset.

If they think you did something wrong because you’re thoughtless or don’t care, then understand your actual reasoning behind your error, it can soften them up.

“It’s trying to help the other party understand how this happened in a way where they can understand that it was a mistake or an error,” says Lewicki. “It’s an effort to put them in your shoes to get a sense of how and why it happened.”

3. Acknowledge your responsibility.

This is hard for some people because it requires them to step out from behind their ego and defensiveness, then fall on their sword.

But if you did something wrong, you just have to own it.

This is key, as it can signal to your partner that you’re aware of your actions and accept your role in them.

A non-apology or shifting of the blame will only make things worse here.

“This is saying, ‘I was wrong when I did that and I accept responsibility for my actions,’ ” says Lewicki. “As opposed to saying something like, ‘the Devil made me do it,’ or some other effort to put the blame on somebody else for what happened.”

4. Make a declaration of repentance.

Here’s where sincerity really carries a lot of weight.

You have to step up and promise that whatever happened will never happen again.

It’s a promise not to repeat your actions.

“In the second study we did, that turned out to be the most important element. It’s saying, ‘I regret this happened. I’ve learned my lesson,’ ” says Lewicki. “But if you make that promise, then you have to not do it again. Kids are notorious for this. They promise they won’t do X and then 10 minutes later they do it again. If you do that, [subsequent apologies] lose credibility.”

5. Give an offer of repair.

So you’ve said that you’re sorry, but what are you going to do to make it right?

How will you move forward from here?

Letting your partner know that you’re not just sorry in the moment, but that you’ve established a plan to go forward and fix things in the long term, will make the apology go down a lot easier.

“If there were actual damages, you can offer to pay for or repair the damages, or if there were [emotional] damages, then a dozen roses, or a box of chocolates might do the work,” says Lewicki. “I’m serious about that. Token offers of repentance that are above and beyond just the words are often quite symbolic.”

6. Request forgiveness.

Interestingly, Lewicki’s research marked this as the least significant element of an apology.

Provided you nailed the other five (or got as many as possible out of those five), asking for forgiveness is only slightly above being a formality in importance.

“Here’s where the severity of the violation comes in,” says Lewicki. “I mean, if you promised to bring home a pizza for dinner and forgot, that’s different than if the spouse finds that you’ve been seeing another woman. But, if the violation is correctable and the violator shows real intent in not repeating, then it’s much more likely to rebuild fundamental trust, but it’s going to take time. It doesn’t spring back immediately.”

Why an apology isn’t always enough

No matter how well-crafted an apology may be, there may be times when the relationship has simply sustained too much damage, depending on what happened, the status of the relationship beforehand and its history, and the other person's threshold for the pain they felt inflicted upon them, among a variety of other factors that come into play when humans' emotions are involved.

The other person you hurt may appreciate your apology but feel that "actions speak louder than words."

Rather than accept your apology at face value and forgive you upon receiving it, they may wish for you to prove you are true to your word before they can feel comfortable trusting you again.

"Forgiveness is about not taking responsibility for the actions or feelings of another but understanding how you were a participant in a situation," says spiritual coaching expert Rev. Ellyn Kravette. "And if a person is apologizing to you more than once about the same type of situation, each person needs to make some kind of change."

Nonetheless, this shouldn't discourage you or cause you to discount the importance of offering a heartfelt apology, because it's likely still needed to begin the healing process if you have any hope of mending the relationship.

Licensed marriage and family therapist and clinical psychologist Maurie Lung explains, "We talk about the two aspects of an apology, the accountability for the action that caused hurt, and the connection to the heart and care for another. Sometimes this can come in two parts. The immediate can be the accountability, and when emotions settle, can come the connection."

"Each situation teaches us something about ourselves," Kravette adds, "and no situation is all bad or all good."

Her view is that "the apology is 'How are we going to use this to bring us closer... to create more understanding... to get the right kind of help and support for change.'"

Matt Berical is the Deputy Editor of Fatherly, where he oversees the Life section, Newsletters, and Special Projects. He’s an award-winning writer and content specialist with more than 16 years of editorial experience in both print and online publications and was previously a staff editor at Men's Journal, a Senior Editor at Maxim, and a founding editor of Van Winkle's.