It Took Me 36 Years To Sit At The Feet Of Sadness

Crying meant losing you all over again, so I refused.

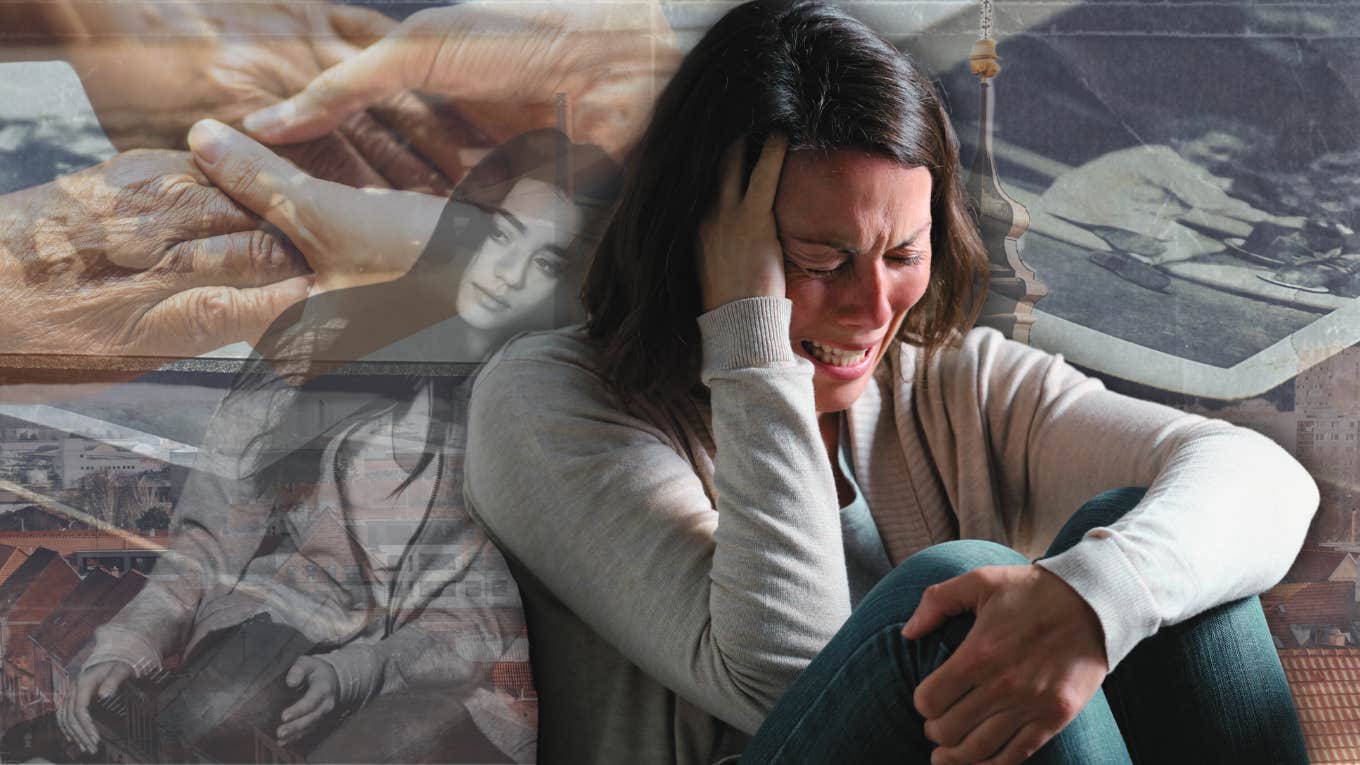

Suzy Hazelwood | Pexels, Martin Katler | Unsplash, inewsistock, pixelshot, Pheelings Media | Canva

Suzy Hazelwood | Pexels, Martin Katler | Unsplash, inewsistock, pixelshot, Pheelings Media | Canva It was the kind of phone call that wielded the power to cleave time. Once received, life would forever be split between the "before" and the "after."

“Hello?” I answered. A pause — a crackling — a tell-tale sign of an international call.

“Jituško?” It was my grandfather, his voice squeezing itself through the 3,500 km of cable lying on the bottom of the Atlantic.

“Ano,” Yes, I said. “Babička zemřela.” Grandma died.

The reason my mother wasn’t at home to take the call is lost to time. What I do recall is heaviness entering my body at the realization that I’d have to be the one to tell her her mother died.

I held my mother as she cried, while on my insides, invisible to anyone, I felt ashamed of my eyes that remained dry. There must be something wrong with me, I remember thinking. My adult life was just beginning. I was getting married, wanting babies, getting promoted at work. I told myself my busyness must be the reason for my emotional disconnect. The tears and grief would come later. They didn’t.

My grandmother, Alžbeta with my grandfather, Michal | Photo from author's archives

My grandmother, Alžbeta with my grandfather, Michal | Photo from author's archives

Dear Grandma,

The last time I saw you as a child was in August of 1979. It was the eleventh summer I had spent with you and Grandpa since I was two. Every year, Mom would ship me off to Slovakia for a few weeks.

When I was little, it was because my chronic bronchitis improved away from the polluted air of Liberec, and as I got older, I wanted to go. I looked forward to my visits with you and Grandpa.

That final August, I knew nothing of my parents’ plan to escape our homeland. I felt perplexed by my mother’s loud outburst of sadness when we pulled away from your apartment, you and Grandpa standing at the doorway waving like you always did.

I waved back until we turned the corner, and you disappeared from view. My parents told me we were off to Bulgaria — a short family camping trip before school resumed. You didn’t know we weren’t coming back, and neither did I.

When instead of Bulgaria we crossed the border into Austria, my mother turned around in her seat to tell my sister, stepbrother, and me that we were escaping Czechoslovakia and the plan was to immigrate to Canada. When I asked when we’d be coming back, she answered, “Never.”

I sobbed uncontrollably. It felt as though I was being torn in half, knowing the two halves could never be reunited. I cried the entire weekend we were held in quarantine at the refugee camp in Transkirchen — three of us to a mattress on the floor. I begged my mother to send me back to live with you. She refused, insisting you were too old and my place was with her.

I wonder now what my life would have been like had she agreed to send me back to you. Whether we’d till our love and I’d grow into a different person, one with less scar tissue on the inside. Perhaps I had cried all the tears then, leaving my riverbed of grief dry.

My sister and I went back to visit Czechoslovakia in 1987. It was still run by communists at the time, and the only reason we were allowed to return was because we were minors when our parents took us. I had just turned 21. My biological father picked us up at Ruzine Airport in Prague and agreed to drive us the four hours to Trenčín to visit you and Grandpa.

It had been eight years and hundreds of letters since I last saw you. You remembered me as a child and I was a woman now.

We entered the apartment building, with its row of mailboxes on the left. (How many times did you open yours only to find it empty and feel the punch of disappointment?) I climbed the one flight of stairs inhaling the familiar scent of plaster and stood in front of your door, my finger hovering over the round doorbell.

You had been sick for many years with Rheumatoid arthritis and heart trouble. As a child, I remember when you had to give up needlepoint because your hands shook too much. You took up crocheting, knitting, and cross-stitching instead; your hands never idle for long.

When I saw you again, you looked diminished sitting on the day bed in the living room, a scarf covering your head. We loved each other so much when I was a child and seeing you that way aroused tremendous guilt in me. My mother, your only daughter, moved across the country when she was sixteen and then across the world when she was 30 taking me with her. And still, at 21, I didn’t know what questions to ask to truly know you.

It’s been 36 years since that phone call. Life has finally afforded me space to feel everything I couldn’t in the past.

My chest hurts at all the memories flooding in. The afternoons I’d spend creating at your kitchen table while you and Grandpa napped. The walls were painted yellow, and the window seemed to always be open to boxes of red geraniums that I never saw you plant but were magically there every summer.

I remember your patience, the way you never told me I was too young to try anything I saw you doing. I wanted to sew clothes for my doll and you brought out a basket of fabric scraps, leftovers from the floral dresses you had sewn for yourself. That final summer, I picked out the yellow cotton fabric. I drew a pattern for a pair of pants for my doll. I cut it out from the cloth and sewed using a backstitch, careful to make each one short like you showed me. I learned to crochet sweaters, dresses, and hats for the doll with blond hair. I remember when on the long train ride home one summer, you gently took her from my hand and combed her hair with your brush, taking each ringlet and twisting it around your finger. We’d spend afternoons pouring over Dorka Magazines, picking out patterns to knit and crochet, or you unraveling old sweaters and I rolling the yarn into giant balls we later used to knit a new sweater.

You made the best cream of carrot soup. When I asked my mother decades later whether she remembered how you made it, she said she could probably replicate it. It was not the same as yours.

In your living room, above the day bed and its shelf of books you kept behind sliding glass, hung a framed needlepoint tapestry you made before I was born. As a child, I’d study the thousands of colorful stitches that together created a picture of a woman wearing a long dress and holding a chubby child on her lap. I now know it to be an image of Madonna and Child, but then, all I saw was a mother’s love for her baby. Grandpa donated it to your church after you died. I wish I knew where it was. I’d go in search of it and bring it back. But that’s just it. I can’t bring you back. I can’t go back to when I was 21 and ask you all the questions, woman to woman.

I’d like to know how it was for you to be a mother to my mother, who is not able to be the kind of mother I need her to be to me. I’d ask you the story of how you met Grandpa and whether you still loved him when I heard you arguing in Hungarian when you thought I was asleep in the mornings. I’d take your hand in mine and ask you about the child you lost before my mother came along. I’d want to talk to you about how you survived the war and when it was over, why you took the train from Budapest and settled in Slovakia.

And most importantly, I’d want to apologize for my selfishness. For not writing to you more.

I recently came across some letters you mailed me before I married my first husband. You had asked if we could travel to see you and have another ceremony with you present. You even offered to pay for the flight. I completely forgot you had asked me. I must have thought it impossible at the time and then, you were gone. I’m sorry. I wish I had made it happen for you.

Tears finally flow as I feel you all around me. I’m overcome with memories of you, and it is good. I can cry at last and know that my love for you was real.

Judy Walker writes about the gritty, lovely, naughty, and joyful bits of humanhood. She has written extensively for Medium and Elephant Journal.