The Most Terrible Poverty Is Loneliness

Social isolation can be a killer, and not just for the elderly.

Plato Terentev, aldomurillo | Canva

Plato Terentev, aldomurillo | Canva The hardest part about moving from California to Nevada was springing the news on my elderly mother.

I worried that it would be a tough sell. Mom liked her assisted living community, even though their services were getting expensive and her advanced Parkinson’s Disease would soon require a higher level of care.

Photo by author

I had recently retired from my law enforcement career.

My years as police chief meant that everyone in town knew me. As much as I loved the community, my true nature is introverted, and the thought of complete anonymity in a new town appealed to me. Also, my wife grew up in our small town and yearned for change and new experiences.

I rehearsed in my mind all the reasons for the move.

I explained to Mom that my son wanted to attend UNLV (University of Nevada Las Vegas) to study computer science. And that several of our retired friends lived in Nevada, enjoying the endless amenities of Las Vegas and the financial benefit of no state income tax.

"We’ve already found an amazing house," I told her.

She eyed me warily and said, "But what about me?"

"Well, naturally, we want you to come with us," I said. "I’ll find you an excellent assisted living community, with even better care than you’re getting here."

She paused for a moment, looked around her small apartment, and then back at me.

"Oh Johnny," she said, "You know I’ll always go wherever you are. What would I do without my Tweetyboo?"

Tweetyboo was one of the ridiculous childhood nicknames she had for me. Mom had a gift for silly nicknames.

Dad passed away years ago, and my sister lived many miles away. By default, I became my mother’s caretaker. Due to her advanced age, she had few friends left. She relied on me for shopping, doctor appointments, financial affairs, taxes, and more.

In many ways, I was her rock.

Looking back, I imagine my mother felt like her whole world was falling apart.

When Dad died in 2004, Mom was alone in the family home (which was located remotely in the hills). Back then, her Parkinson’s Disease was less severe, but without my father’s help, the house and grounds were too much to maintain. She decided to sell the house and purchase a smaller one in the city where I lived and worked.

Mom needed to be close to me, my wife, and my son.

For several years Mom enjoyed her new home, where she often babysat my son and occasionally threw parties for family and friends. But eventually, her Parkinson’s advanced. No longer able to drive, she decided to move into the town’s only assisted living center.

"The loneliest moment in someone’s life is when they are watching their whole world fall apart, and all they can do is stare blankly." — F. Scott Fitzgerald

We got her a motorized mobility scooter, which she used to visit the dining hall. But over time, she could no longer operate the scooter, and meals were brought to her room. Lollypop, her small cat, kept her company, but Mom missed socializing in the dining hall.

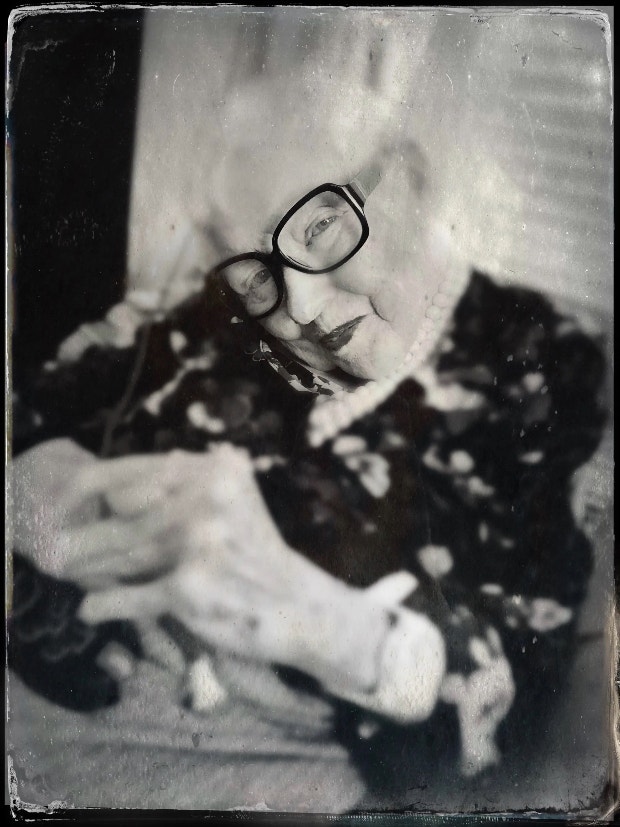

Photo by author

I brought groceries every weekend to my mother, and we’d visit for a few hours. But my job as police chief was demanding, and it was hard to visit more frequently. Thus, we hired my wife’s sister to visit my mother, tidy up her apartment, and provide some much-needed socialization.

My mother and sister-in-law became fast friends.

Eventually, the day came to move my mother to her new assisted living apartment in Nevada.

My wife and her sister took my Mom to the airport and flew her to Las Vegas. They managed Mom’s wheelchair, hailed a handy cab, and soon arrived at my mother’s new home, Sunrise Senior Living.

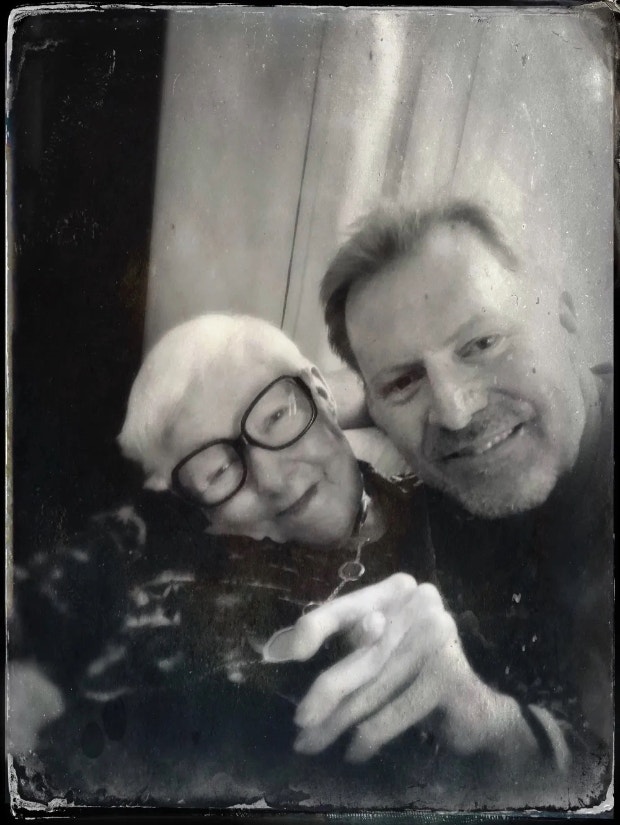

With Mom at Sunrise Senior Living | Photo by author

The entire staff lined the entrance to the facility to greet her. She felt like royalty. In advance, we had already moved all her things into her new apartment. She was thrilled with the room, the beautiful mountain views, and the caring and professional staff.

Staff members often visited my mother during their shifts, since Mom always kept her room stocked with cookies, sodas, and ready conversation. Mom would offer life advice to the young women and enjoyed hearing about their work, families, dreams, and struggles.

Over time, Mom’s Parkinson’s Disease worsened.

A lifelong reader, Mom’s tremors denied her the ability to hold a book and read. We found a local company that provides support for the elderly, and we hired a woman named Suzanne to read to my mother twice a week.

"Loneliness is my least favorite thing about life. The thing that I’m most worried about is just being alone without anybody to care for or someone who will care for me." — Anne Hathaway

While I visited my Mom as often as I could, I knew it was important for her to have others to talk to and confide in. Thankfully, Suzanne and my mother had many things in common and became fast friends.

But eventually, time runs out.

She had been ill and losing strength, and my wife (as a hospice nurse) warned me that Mom was fading. Hospice was arranged, and despite the COVID-19 pandemic, I was allowed to visit.

With each visit, I donned a gown, rubber gloves, and mask. I’d sit beside her bed and reminisce. Mom did her best to talk.

Then one day my mother’s favorite aid phoned me to say that I needed to get there quickly. I jumped in my vehicle and raced over. I put on all the protective clothing and mask, took the elevator to her room, and sat beside Mom.

Her eyes were shut, her breathing labored.

I held her hands, stroked her hair, and told her how much everyone loved her. I repeated over and over, "I’ve got you," as her breathing slowed. I wanted her to know that she was not alone.

She passed away quietly in my arms.

In 2018, Britain established a new government position known as the "Minister for Loneliness."

And Britain is not alone. Other countries, like Japan and Sweden, have similar positions.

The reason for this is that loneliness has become somewhat of a public health crisis.

According to a New York Times essay by Nicholas Kristof:

"Loneliness crushes the soul, but researchers are finding it does far more damage than that. It is linked to strokes, heart disease, dementia, inflammation, and suicide; it breaks the heart literally as well as figuratively.

Loneliness is as deadly as smoking 15 cigarettes a day and more lethal than consuming six alcoholic drinks a day, according to the surgeon general of the United States, Dr. Vivek Murthy. Loneliness is more dangerous for health than obesity, he says — and, alas, we have been growing more lonely. A majority of Americans now report experiencing loneliness, based on a widely used scale that asks questions such as whether people lack companionship or feel left out."

Social isolation can be a killer, and not just for the elderly.

Despite the promise of social media to bring people together, it’s a poor substitute for real human interaction. The energy of a lively conversation, the gaze of a friend who cares, and the touch of a loving hand on your shoulder, fill your soul with a sense of belonging, contentment, and happiness.

"The most terrible poverty is loneliness and the feeling of being unloved." — Mother Teresa

In his article, Kristof quotes Paul Dolan, a professor of behavioral sciences at the London School of Economics.

Dolan notes that "We’re not meant to be lonely as a species," and "If you were to think of the most significant interventions to improve life expectancy, after quitting smoking, it’s: Don’t be lonely."

Over twenty years ago, the American political scientist Robert D. Putnam published his book, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. I read the book years ago, and sadly, things have gotten worse.

An Amazon reviewer noted the following:

"Bowling Alone traces the rise and decline of America’s organized social institutions over the course of the twentieth century, including everything from Elks and Kiwanis to the Sierra Club and Boy Scouts to churches and bowling leagues. Putnam shows, with an immense amount of hard data, how membership and participation in all of these organizations swelled in the middle decades of the twentieth century and then went into steep decline in the mid-late 1960s."

The reviewer goes on to write:

"Not only did membership in social groups wane during this era, but general participation in civic life atrophied as well. People attended fewer community meetings, fewer political rallies, wrote fewer letters to newspaper editors, and attended church less often. People even entertained guests and attended dinner parties less often than they used to."

Putnam blames several factors for society’s growing isolation.

Things like two-income families, in which both come home exhausted and uninterested in social functions or volunteering. Mobility and sprawl play a part, whereby people don’t put down roots. And most of all, Putnam blamed technology and the rise of mass media.

Putnam notes that before television, people went out with friends and neighbors because spending night after night at home was boring. After television, people got addicted to watching programs instead of socializing.

Putnam published his book in 2001, before the rise of Facebook, TikTok, and the rest of social media’s addictive algorithms and predatory attention economy.

No doubt, the Internet has made it easier than ever to connect with like-minded people. And sometimes, social media can help people feel less alone. But it will never replace the benefits of real, face-to-face interaction.

During my law enforcement career, some of the saddest people I encountered were also the loneliest.

Some had lost loved ones and friends and found themselves marooned in an unfamiliar landscape of solitude and creeping isolation. Others may have had spouses and family, but they were devoid of love and connection.

Sometimes, a dead relationship can be the loneliest thing of all.

Even the young cannot escape the grip of loneliness. As a juvenile detective, I often taught safety programs in the schools. Some children used to glom onto me, holding my hand or excitedly talking about pets or imaginary friends.

I didn’t know what conditions in the home led to such lonely children, but the sadness in their eyes and their desire for connection broke my heart.

Of course, that was years ago, and the loneliness epidemic has only gotten worse. Everywhere I go today, I see people glued to their smartphones. Kids and adults are addicted to silly videos on TikTok, video games, and superficial YouTube videos.

"The tycoons of social media have to stop pretending that they’re friendly nerd gods building a better world and admit they’re just tobacco farmers in T-shirts selling an addictive product to children. Because, let’s face it, checking your 'likes' is the new smoking." — Cal Newport, Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World

There are fewer random conversations and social interactions. And it’s getting harder to chat with people. They tend to be wary, and anxious to get back to their phone.

The only time I see my neighbors is when I take my dog for walks.

No wonder some countries have created loneliness ministers.

They’re trying to build up the infrastructure that enables social connection, which includes physical infrastructure. Things like parks and libraries, and a social infrastructure to get volunteers or enthusiasts with similar interests together.

My favorites are the "chatty benches" established in England, Sweden, and Australia.

Kristof writes in his essay:

"This is a park bench with a sign encouraging strangers sitting there to chat with each other; in a Northern Ireland town, the sign says: 'Sit here if you are happy to chat with passers-by.'"

Kristof adds:

"There are also 'talking cafes,' where people are encouraged to gab with other coffee drinkers. There are 'libraries of things,' where you can mingle with neighbors to borrow camping equipment or a carpet cleaner or lend out your own gear.

Solutions to loneliness are like that — little nudges to encourage us to mingle the way we evolved to. They’re so easy, and loneliness seems so debilitating, that we should be doing more."

Indeed, we should be doing more.

How about you? Are you lonely?

There’s a difference between being alone and being lonely. For example, I require a great deal of solitude. I like to read, write, think, walk my dogs, and get lost in my thoughts. My friends tease me over my somewhat monastic habits, but I like being alone with myself.

"The greatest thing in the world is to know how to belong to oneself." — Michel de Montaigne, The Complete Essays

For others, being alone makes them feel lonely. And in the end, we all require some degree of human connection.

Diving into your creative passions can help, and many defeat loneliness by taking art classes, writing workshops, volunteering, etc. There are many opportunities and ways to connect with others, if you’re willing to risk a little and try new things.

The best strategy to overcome loneliness is to take action.

That’s what my wife and I did for my mother. We took action. We hired my sister-in-law to visit my mother and help her.

Then, in Nevada, we hired a woman named Suzanne to visit with and read to my mother. To keep her company and have someone to confide in.

And when the time came to say goodbye, I thank God that I was able to be with my mother in her final hour.

To hold her.

To tell her she was loved.

To say, "I’ve got you."

To let her know she wasn’t alone.

John P. Weiss is a writer and former police chief with over twenty-six years of law enforcement experience. He is the author of What Life Should Be About: Elegant Essays on the Things That Matter, and his work appears in The Guardian, Medium, Simplify Magazine, Becoming Minimalist, Good Men Project, and elsewhere online.