The Tragic History Of American Indian Boarding Schools — And Why You Should Care

There are hundreds more like Kamloops Indian Residential School

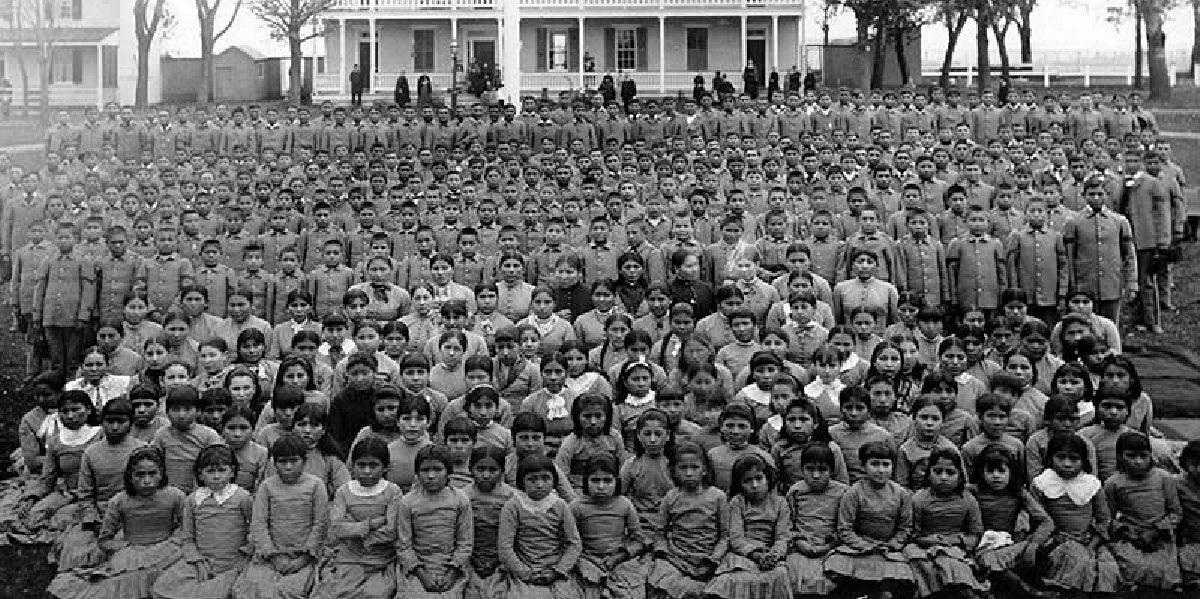

By Unknown author - Unknown source, Public Domain

By Unknown author - Unknown source, Public Domain First Nations people are mourning for the lost souls found in the mass grave near the Kamloops Indian Residential School.

For indigenous people, they aren't just 215 dead bodies. They are our lost relatives.

Families were forced to send their children to these schools and far too many times, they never made it back home.

The "education" indigenous children receive in such institutions is sometimes described as forced assimilation.

It's actually genocide.

These schools began in the late 1800s and were all over the U.S. and Canada.

In 1860, the Bureau of Indian affairs established Indian boarding schools, where Native American children were taken from reservations and assimilated into the white American standard of living. In Canada. Reports of the schools began in the 1880s.

In 1920, Canada passed the Indian Act which made it mandatory for all indigenous children to attend residential schools, making it was illegal for them to attend schooling elsewhere.

Richard Henry Pratt, head of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, founded in 1879, used the motto “Kill the Indian, save the man.”

In these institutions, children were beaten, sexually assaulted, and shamed for speaking their language or trying to take part in cultural practices.

The Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement identified 139 residential schools in Canada, although that number does not include schools run by provincial governments or religious orders.

And according to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, there were as many as 367 such schools in the U.S.

The sites of these schools are now filled with unmarked graves, which means that in the U.S. and Canada, it's likely there are at least 506 mass graves full of hidden bodies and buried traumas spanning generations.

The laws pertaining to these schools weren't the only regulations put in place to keep indigenous people "assimilated."

In 1883, the United States passed a religious crimes code that banned native people from practicing “native dancing and ceremonies, including the Sun Dance, Ghost Dance, potlatches, and the practices of medicine persons.”

Indian agents used force, withheld rations and resorted to imprisonment when they found native people breaking this rule.

Generations of young adults were raised without passing down knowledge or teachings of their culture because they felt shame about who they were.

It wasn't until the 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act that these ceremonies were made legal again.

"I remember coming home and my grandma asked me to talk Indian to her and I said, 'Grandma, I don't understand you.' She said, 'Then who are you?'" — Bill Wright, PR

It is easy for news sources to spend two short paragraphs to say that these schools operated as institutions of genocide where children were physically and sexually abused, used for labor and punished for having anything to do with their culture.

But it isn’t so easy to accept that the mass grave recently uncovered wasn't an isolated incident.

There isn’t a clear number of children known to have been taken from reservations, but it is thought to be in the hundreds of thousands — an estimated 150,000 First Nations children in Canada.

That means there are thousands of these stories that for years have been kept within families and communities.

And that means there are thousands of bodies hidden.

The Church, the United States government and the Canadian government should investigate the crimes committed in these schools.

But to do that, they would need to accept their role in cultural genocide.

“Although she died in 2011, I can still see her trying to outrun her invisible demons. She would walk across the floor of our house, sometimes for hours, desperately shaking her head from side to side to keep the persistent awful memories from entering.” — Mary Annette Pember, The Atlantic

Over the years, people have spoken out against the abuse they faced in residential schools.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada was created in 2007 to address the truth of what happened and begin to take steps to reconcile with those directly affected by the schools.

The goal of the commission was to educate people on what happened in the residential schools. They spent $72 million dollars to go from nation to nation in Canada, interview 6,500 survivors to collect their stories and educate people are the dark foundation of Canada’s Histories.

In 2009, this commission requested that Indian Affairs cover the cost of identifying unmarked graves at residential schools. It would have cost $1.5 billion. The request was denied that December.

The closest the United States has gotten to an acknowledgment of the treatment of native people was the Native American Apology Resolution on December 19, 2009, which apologized for past “ill-conceived policies toward the Native peoples of this land.”

But these were just words that were silently said with no promise of investigation or accountability for their crimes.

“When I came home, I started fighting with my family. I didn’t feel like I had a home. I didn’t feel like I was a part of my family. I started trying to find ways to deal with the anger and pain I felt. I started drinking when I was very very young, and it became my form of self-medication and a coping mechanism that I used for over 30 years of my life.” — Eddy Charlie, The Nature Of Us

In September 2020, the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policy Act was proposed by Deb Haaland and Elizabeth Warren.

This bill was meant to address the cultural genocide and human rights violations that occurred in the Indian Boarding Schools.

It was never passed.

If it had, the United States government would have had to admit that what they did to tribal communities was genocide.

"Don't try to see what can [you] do. We want people to hear this story for us. It's not a fairy tale. It's not something from one of the Stephen King novels. This truly, really happened to 150,000 children." — Eddy Charlie, All Points West

This tragedy doesn’t just bring light to what happened but brings back the trauma for survivors.

Eddy Charles, a survivor of the Kuper Island Residential School, tells people that the best thing they can do right now is to listen to the stories of the survivors.

Others are finally telling their stories as a call to action. All too often, children were told that no one would believe them if they spoke out against abuse, that is was imagined, and their trauma and identity invalidated.

Tribes are taking steps to revitalize their cultures and redefining what cultural revitalization looks like for them. Part of it is addressing the traumas that led to teachings and languages being lost.

These schools were instrumental in the partial fracture of culture and language. Somethings will always be lost but the work tribes have done to become stronger as a culture and as people shows that identity cannot be beaten out of someone.

Opening up the conversation about the treatment of indigenous people in the US and Canada means addressing and taking responsibility for genocide. This will open wounds and bring back trauma but will establish that this did happen.

There isn’t a number yet for the bodies hidden at and around these schools, but hopefully, by uncovering them, tribal communities can find ways to can move forward and learn how to talk to their elders who do not yet have a language for their trauma.

Leeann Reed is a writer who covers news, pop culture, and love, and relationship topics.