'Defund The Police' Doesn’t Mean That 911 Calls Go Away — It Means Something So Much Better

It means using the right people for every situation.

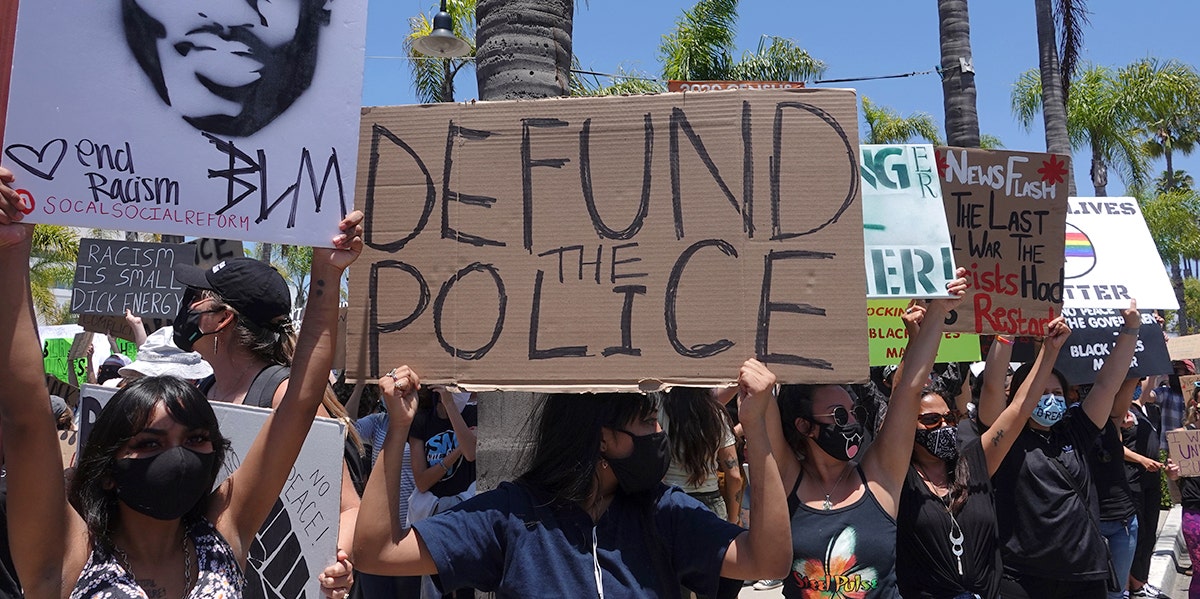

Simone Hogan / Shutterstock

Simone Hogan / Shutterstock Many people hear the phrase “defund the police” and immediately think in reactionary terms. They think that 911 is going away, or emergency services will disappear, or crime-fighting as we know it will be a thing of the past.

But none of that is true.

What is the 'defund movement' and what are the alternatives to policing?

The defund movement comes from the idea that there are better options than continuing our current emergency response system.

That's because police officers aren’t trained or established to successfully control all situations — and they shouldn't be expected to. They have a primary responsibility, and provide extraordinary assistance to people within specific parameters.

Otherwise, as we have often seen, the police can be a danger to citizens. The recent anniversary of the murder of George Floyd is a stark reminder of this.

Ashley Southall, the Metro Police Bureau Chief for the New York Times and moderator of the panel “Envisioning Alternatives to Policing” at the Museum of the City of New York, says that the primary role of police is fighting crime, and they should be allowed to focus on that role.

While Southall doesn't speak for defund, she pulls from her vast experience in dealing with police shootings and criminal reporting to shed light on what can be learned from our knowledge about why they happen.

Outside of tackling criminal behavior specifically, a run-in with the police can escalate into something else entirely.

RELATED: Defund The Police: The True Human Toll Of Racism In American Policing

“They’re largely negative experiences for people,” Southall tells us. “We don’t send the police to arrest someone for fun.”

Officers are trained to respond to situations with lethal force. And even when they possess additional training that fits a particular disturbance, they often proceed as if they didn’t have that training at all. Like in the recent case of two Grandview officers who were trained at crisis intervention but still killed a 17 year-old boy who was reported as suicidal.

In addition to reducing unnecessary conflict in emergencies, providing an opportunity for other support services to respond to certain calls would actually free up the police force to use their resources and manpower for the tasks they’re actually intended for.

Southall says that the goal of the defund movement isn’t to turn away from the police at all. It’s to address the issues that require police intervention in the first place.

Instead of police officers showing up to every call for help, even when the use of force isn’t required, social workers and mental health professionals can respond instead.

Adding in additional services for responding to complaints opens the door for a wider range of assistance for those in need. And Police might not be the answer every time.

“They have a lot of functions that are tangential [to crime fighting], and they take aware resources and manpower from that mission. There’s been this complaint for years that their responsibilities were too broad. If you think about it, the goals of Defund, which is to restrict the role of police, and the departments who complain about being stretched too thin, are largely the same.”

How would alternatives to policing help in reality?

Many are curious about the effectiveness of a police force spread too thin. And when violence is often the only approach, even though violent crime is on a steep decline, just how likely is it that crimes will be solved, anyway? It turns out that we’re entering a phase in policing where clearance rates are dropping, leaving many criminal acts unsolved and unpunished. This comes as the U.S. already sees lower clearance rates than countries in Europe.

“You have to wonder,” says Southall, “if you reversed our reliance on the police to do all these other jobs, and decided that we can handle them differently, whether that would free police up to invest more in solving crimes.

“There’s a lot of pain in communities where police have been used aggressively and yet many murders remain unsolved. And in some cases you can go to those communities, and they’ll tell you ‘Oh we know who did it, he was just never arrested or charged.’ And when you ask why that is, people just don’t trust the police.”

What do alternatives to policing actually look like?

There’s a reason that we hire dedicated support staff to care for those who suffer from mental health conditions. There’s a reason that psychiatrists and licensed social workers train for so long in order to serve the public. They, too, have specific roles to play in society. For police, who train for under twenty weeks and often don’t receive instruction for how to deal with people in crisis, it could be time to forward those calls.

“Mental health calls are a small part of 911 calls in New York City,” says Southall. “Out of those about one in four involves some kind of weapon or threat. The remainder are potentially harmless. Those usually involve someone experiencing paranoia or delusions or someone yelling on the street for no reason. Before defund the police, there was already an effort to send social workers out with police to respond to calls for someone experiencing a psychiatric or emotional issue.”

In Oregon, a program called CAHOOTS has been ongoing for 31 years. First responders are trained to address people undergoing a mental health crisis. They’re unarmed, trained to address mental illness, homelessness, and addiction, and specialize in conflict resolution de-escalation, welfare checks, and more. Teams consist of nurses, paramedics, and EMTs.

In 2019, out of all 24,000 CAHOOTS encounters with the public, only 150 ended with calls for police backup. They’ve never been responsible for a fatal encounter or serious injury.

Many cities are considering the adoption of the CAHOOTS model, or creating hybrid programs that would send specially trained personnel out with police to handle situations that don’t require threats of authority and force.

In England, unarmed, uniformed police staff called community support officers are utilized to respond to disturbances. They can’t respond with force, and handle the lion’s share of calls. Only 10% of police officers in England carry firearms.

There are additional proposals that are gaining traction, too, things that have been either attempted elsewhere or theorized about long before our current moment of need. Community mediators, community self-policing, and additional access to mental health services are all on the table.

How do we get police alternatives to take hold in our communities?

The more people notice about the way their services function in society, the more likely they are to adapt for the better. We’ve been here before, but at no other time have we seriously entertained so many policing alternatives and actually implemented them into the first response toolkit.

Panels like the one put on by the Museum of the City of New York that Southall is moderating continue to bring more attention to the issues and educate the public on the key points. Raising awareness for the gritty details is one of the best ways to establish a solid foundation for a public argument to push for change.

The more cries for justice we have for George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Adam Toledo, and others, the faster the momentum will take us into a future where policing isn’t just changed for the better, it’s no longer necessary at all.

“The goal is not to throw away the police,” says Southall, “the goal is to make them obsolete. And that requires crime to go away. For crime to go away, you have to address what’s creating the problem.”

Kevin Lankes, MFA, is an editor and author. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Here Comes Everyone, Pigeon Pages, Owl Hollow Press, The Huffington Post, The Riverdale Press, and more.