Loophole From 1887 Allows Woman To Call Her Own Trial After She's Told Rape Case Was Just 'Immature Sex'

Prosecutors dismissed her case, but she's found a way to take back her power.

YouTube / CBS

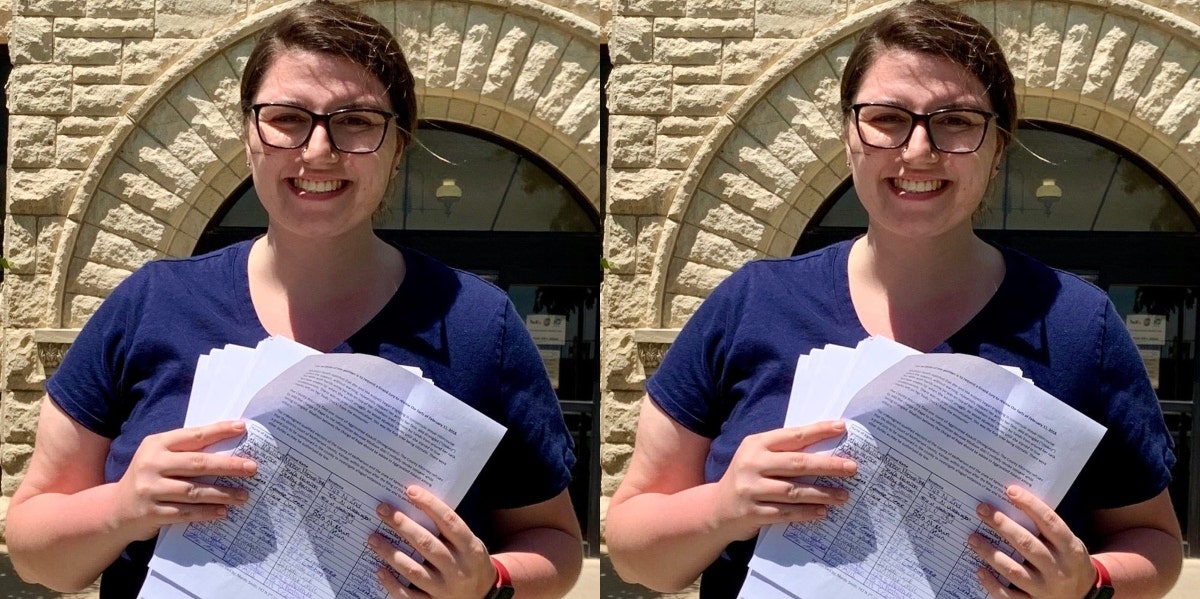

YouTube / CBS A Kansas rape survivor will have her story heard in front of a grand jury that she convened herself after prosecutors refused to pursue a rape charge against the man she claims attacked her.

Madison Smith has invoked a 19th Century law that allows her to make her case after years of being pushed out of the courts.

By way of a petition, 22-year-old Smith has been able to skirt county prosecutors’ refusal to deem the incident rape and will now have an opportunity to pursue a conviction she’s been seeking for most of her time as a college student.

Madison Smith alleges she was raped by a friend in 2018.

In 2018, Smith alleged she was raped by a classmate at Bethany College, a Christian liberal arts college in Lindsborg. What began as consensual sex with a friend in his dorm room escalated to assault as Jared Stolzenburgallegedly began strangling her, making her unable to say “no.”

Smith says she tried to fight off Stolzenburg and repeatedly lost consciousness during the incident. A forensic report taken the following day noted bruising on her neck and inside her mouth.

For three years, local prosecutors refused to hear her case claiming that a withdrawal of consent was not communicated to Stolzenburg.

Smith recalls McPherson County Attorney Gregory Benefiel repeatedly diminishing her claim.

“He told me that the rape I experienced wasn’t rape, it was immature sex because I didn’t verbally say no when I was being strangled,” she said in one court hearing.

Eventually, Stolzenburg was found guilty of aggravated battery and received two years of probation, but Smith says the charge was inadequate and revictimized her.

Smith is using an 1887 Kansas law to convene her own jury.

By this time, Smith and her parents had begun pursuing other options. After hearing a podcast interview with Justin Boardman, a retired police officer who now trains police and prosecutors to investigate sex crimes without retraumatizing victims, Smith’s mother reached out.

Boardman pointed the family to an 1887 Kansas law that was invoked during the Prohibition era to get around prosecutors refusing to take action in temperance laws.

To convene their own grand jury, the Smiths needed to acquire 329 signatures or 2% of the voting county’s voting population plus 100.

Smith retold her story to stranger after stranger in a hair salon parking lot until the signatures were acquired. Then, when the first petition was rejected on a technicality, did it all over again before a panel approved the request.

A judge has set Sept. 29 for the grand jury to begin. Mandy Smith, Smith’s mother, will speak first as her name is the first signature on the petition.

The case is symbolic for rape survivors who don’t get justice.

Smith acknowledges that the jury may not return the indictment she wishes, but she's satisfied in her efforts.

“We tried everything we could, and we exhausted all our resources. I’ve got to know I tried,” she says.

The case has become about pursuing all channels in a system that often disregards sex crimes and their victims. Less than 1% of rapes lead to felony convictions. And those are just the assaults that get reported.

Because of the inordinate shame and the lack of investigation around sexual assault, 2 out of 3 sexual assaults go unreported. Survivors fear their cases will not be heard or their claims will be ignored. A fear exemplified by cases like Smith’s.

The 19th Century law employed by Smith explores an opportunity for survivors to advocate for themselves when the system refuses to do that work on their behalf.

This case, and the media attention it is garnering, are proof that victims are in need of something like the 19th century law — but more current — to protect them.

Alice Kelly is a writer living in Brooklyn, New York. Catch her covering all things social justice, news, and entertainment. Keep up with her Twitter for more.